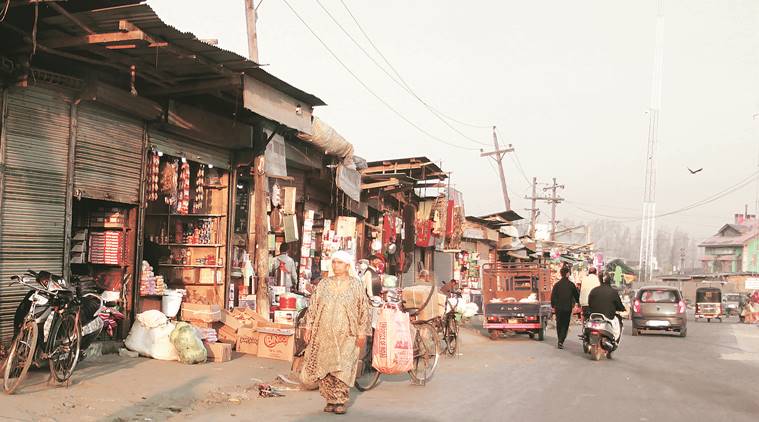

Around 5.55 am, soon after the morning prayers, the silence around the Batamaloo bus stand in Srinagar is broken by the sound of clanging shutters, haggling customers and blaring taxi horns. The relaxation hours for the day, or the “golden hours” as some call them, have begun; and both the vendors and the customers are out to make the most of the time. They only have until 10 am to do so.

Around 5.55 am, soon after the morning prayers, the silence around the Batamaloo bus stand in Srinagar is broken by the sound of clanging shutters, haggling customers and blaring taxi horns. The relaxation hours for the day, or the “golden hours” as some call them, have begun; and both the vendors and the customers are out to make the most of the time. They only have until 10 am to do so.

Following the killing of Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani on July 8, business in the Valley has been crippled by a series of protests, curfew, clashes and shutdowns, with the economy suffering losses of an estimated Rs 10,000 crore. While curfew continues to be in force in parts of the Old City, in other regions, shopkeepers have been abiding by the ‘protest calendar’ issued every Wednesday by the separatist leadership.

The calendar declares specific hours — 5 pm to 9 pm and 10 pm to 6 am on specified days — for traders, shop owners and transport companies to conduct business. However, with more and more people stepping out to stock up on their supplies and travel to the interior parts of the state, traders have informally extended the relaxation hours and now keep their shops open from 6 am to 10 am as well.

“According to the schedule declared by the separatists, the relaxation hours end at 6 am. But because there is no business at night, we open our shops only after 6 am. We have begun stretching the relaxation time to 10 am in the hope of making some money,” says Mehraj-ud-din, a toy shop owner in the Batamaloo market.

Sitting behind the counter of his 10×12 sq ft shop, the 45-year-old complains about his business taking a “severe hit” in the past few months. “My shop was shut for two months. In the past 15 days or so, the rush at Batamaloo has increased, so I have been opening the shop soon after the morning prayers,” he says, carefully packing a few toys for a customer from Baramulla. “There are six members in my family. At least during the relaxation hours I make enough to take care of them,” he says.

With over 300 shops, a bus stop and a taxi depot, Batamaloo, which links the north and central parts of the Valley, is a busy place during the relaxation hours. The shops here sell groceries, footwear, kitchenware, hardware, mobiles and electronic items. But with the unrest in Kashmir continuing for well over 90 days now, most of the shop owners had been staying at home, opening their stores only recently.

A few metres away from Mehraj-ud-din’s outlet, garment shop owner Ishfaq Ahmad, 23, is hoping to find customers to sell off his summer stock. “Winter is almost here and I still have a large pile of my summer stock lying around. I am not even earning 5 per cent of what I used to make before the shutdown began,” he says, adding that he hasn’t bought any fresh merchandise since the turmoil started.

“I only get four-five customers in a day. Most people you see here are in transit, arriving at the bus station in the early hours from rural towns and travelling onwards,” says Ahmad, expectantly eyeing commuters who have arrived at the bus stop.

Yasin Khan, chairman of the Kashmir Economic Alliance, the biggest trade body in the Valley, pegs the trade losses in Kashmir since July 8 at Rs 100-120 crore per day. “The accumulated loss suffered by the business community of Kashmir is over Rs 10,000 crore,” he says.

Mohammad Ashraf Mir, president of the Federation Chamber of Industries Kashmir, points out the other “big problem” confronting the community: repayment of loans. “Almost every trader here has a bank loan they can’t repay. Every sector has suffered massive losses, and even if the shutdown ends now, it will take these men years to compensate for the losses,” he says.

For many, such as Fayaz Ahmad, who owns a furniture showroom on the city’s Residency Road, the shutdown has dealt a cruel blow to their businesses, coming as it has on the back of the devastating 2014 floods. “First we suffered huge losses because of the floods and now these curfews and shutdowns… When are we supposed to conduct business? The government is not taking serious steps to end the impasse, there should at least be some dialogue to end the stalemate,” says the 60-year-old.

By all accounts, it is the transport sector in the Valley that has been the worst hit. Transport companies say over 5,000 vehicles have been standing idle since July 9, and according to government figures, the losses incurred by the tourism sector have been over Rs 250 crore.

“Earlier, over 10,000 tourists would arrive in the Valley every day, and hotels and houseboats would be booked in advance up to September. But as the situation worsened after July 8, all bookings were cancelled. Now, only 400 to 500 tourists, mostly foreigners, visit Kashmir every day, and even they travel to Ladakh after spending a day in Srinagar and Sonmarg,” says a deputy director of J&K tourism, who did not wish to be named.

Back at the Batamaloo bus stand, a dozen cabs, many arriving with passengers from Uri, Bandipora and Kupwara, have queued up, and drivers are haggling with new commuters.

For the past 20 days, says Javid Ahmad Khan, 35, a taxi driver from Kupwara, he has been making just one trip to Srinagar, less than two hours away, compared to three-four he would make before the protests. He says he must make it back to Kupwara by 9 am to “avoid any risks”. “I left Kupwara around 5 am and will go back soon… If I don’t reach home by 9 am, my family will get worried,” says Khan, who owns a Chevrolet Tavera and charges Rs 200 per trip.

“I run my vehicle on alternate days now. It is a risky job. On many occasions, my car has been hit by stones on the national highway. But I need to do this for my family,” he says.

A little after 7.30 am, policemen and CRPF security personnel begin arriving on the main road near the bus stop. Though over 250 buses have been standing idle at the bus stand, some of them have been hired by the police to ferry security force personnel across the city.

“A large number of bus drivers haven’t earned a single penny since the shutdown began. A few fortunate ones have had their buses hired by the police, and earn Rs 3,000 a day,’’ says a driver waiting outside the bus stand.

The shutdown has taken its toll on commuters too. Sayeeda Begum, 40, has had to make special arrangements to keep her doctor’s appointment in Srinagar. Begum is looking for a vehicle that will take her to her home at Sultan Daki in Uri, 105 km away. “Yesterday, I had an appointment with a doctor in Srinagar and had to stay over at a friend’s house because there are no cabs beyond the relaxation hours.” says Begum, who works for the Social Welfare department.

As the sun gets brighter, it is almost time to pack up. Most shopkeepers have done very little business, and are hoping the evening hours are more fruitful. “Innocent boys are being killed by pellets and civilians are being harassed… These protests are necessary to end these atrocities, but we need to earn our bread and butter as well,” says Mehraj-ud-din, pulling down the shutters on his toy shop.

Kashmir’s economy is slowly finding its way around ‘Protest Calendar’ issued by Resistance Group